Participatory budgeting for climate adaptation

Climate change is a hot topic. As a result of climate change and increasing urbanisation, superfluous water is a major challenge for cities.

Changes to the existing urban infrastructure will be needed to be able to manage the increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events. Therefore, climate adaptation is increasingly becoming priority on the municipal agenda. The ‘Deltaplan Ruimtelijke Adaptatie' obliges municipalities to perform stress tests to assess their resilience to climate change. Multiple stress tests that have been performed to date (eg. in Wageningen) show that indeed new integral approaches are needed to be able to manage the enormous amount of precipitation that will ravage our cities.

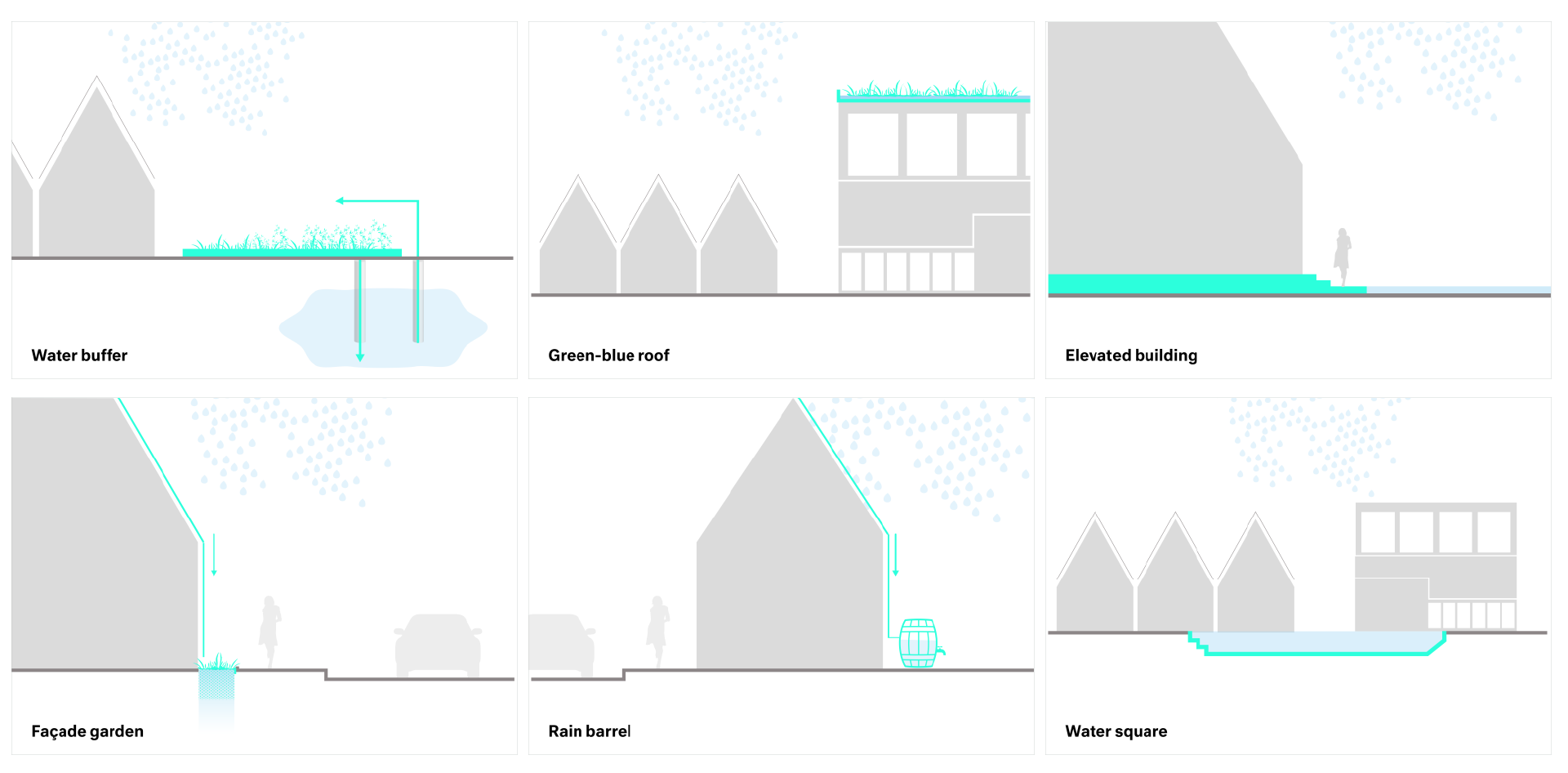

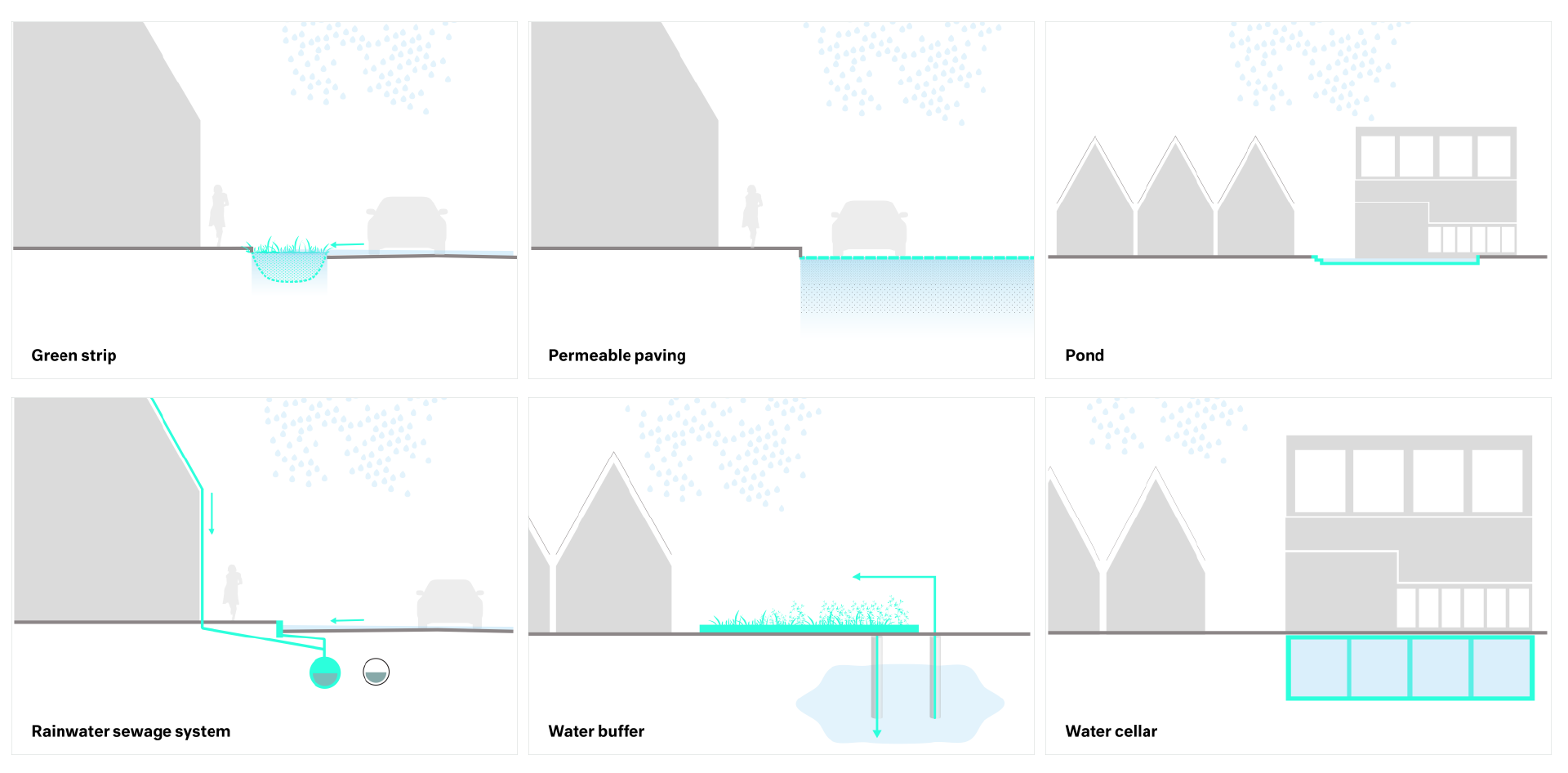

There is a multitude of measures available to improve the resilience of urban areas. Besides solutions such as increasing the sewerage capacity, constructing flood barriers or water-retaining structures and elevating the ground floor of buildings, some other measures resort to the way nature works itself. The so-called Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) are considered to be an essential addition to grey infrastructure. As discussed in our previous blog post on the co-benefits of the Urban Water Buffer in Spangen, NBS provide complementary benefits in addition to their primary function for water management. Many of these co-benefits concern the inhabitants as the actual end-users.

But how can we define the value different measures provide to the end-users and how can we involve inhabitants when planning for climate adaptation?

Defining the value of water management solutions through participatory budgeting.

Together with researchers from the TU Delft and the Municipality of The Hague, we are conducting a research into the value inhabitants derive from various measures (including both grey infrastructure and nature-based solutions) to prevent superfluous water problems in a neighbourhood in The Hague.

For this research, we make use of a participatory budgeting approach called the Participatory Budget Game (PBG). In this method for participatory value evaluation, developed by Niek Mouter (TU Delft), Paul Koster (VU Amsterdam) and Thijs Dekkers (Institute for Transport Studies Leeds), inhabitants are asked to divide a limited budget between a set of possible climate adaptation measures. In this way, inhabitants take the role of public authority, as they are asked to assign the budget in the way they feel the municipality should invest the public budget for climate adaptation.

The underlying mechanism of the PBG is that inhabitants are forced to make trade-offs between characteristics (attributes) of the potential measures. For example, if a measure will result in more green space, it might likely come at the cost of parking places. The effect of a measure on each of the eight attributes is presented to the respondents. Since not all measures can be realised within the budget, the respondents are forced to make a decision based on the scores of the measures on each attribute. Using econometric choice-modelling techniques the relative value of the attributes can be derived from the combination of projects that respondents select. Besides these quantitative results, qualitative insights in underlying motivations of respondents are generated through a few follow-up questions after completion of the PBG.

The PBG was developed as an alternative to other participatory research methods, which struggle with problems like self-selection of respondents and time-consuming procedures. Since the PBG can be completed online in only 20-30 minutes, many more residents can participate and a better representation of the population can be achieved.

What can be done with the results?

Even without performing complex econometric modelling, basic descriptive results of the selected measures provide valuable knowledge for a public authority on the measures preferred by the inhabitants.

Furthermore, the results of the econometric modelling provide sophisticated insights into the underlying motivations of inhabitants to choose for a specific measure. These motivations are based on the effect of a measure on the attributes, such as extra green areas, participation by residents and water re-use. It allows for a comparison between the importance of each attribute for the inhabitants. Like how much parking spaces inhabitants would be willing to give up, in exchange for an additional 40m2 of green space.

These outcomes may not directly result in a design for the district, but provide focus points for vision and plan development. The role of the inhabitants is not to give their opinion on different design possibilities but to contribute to the drafting of a program of requirements. The PBG thus prevents NIMBY discussions, making it possible to include the collective belief of inhabitants in the link between municipal visions and project-specific implementation plans. A collective belief that is not just based on the opinion of a few participants joining a session in a town-hall, but based on a significant representation of the population.

Do you want to know more about the application of Participatory Budgeting approach in the planning and development of climate adaptation projects?